NASA Astronaut Scott Kelly's Heart Shrank by One-Third

Prolonged exposure to weightlessness causes the human heart to significantly shrink in size

2/7/20253 min read

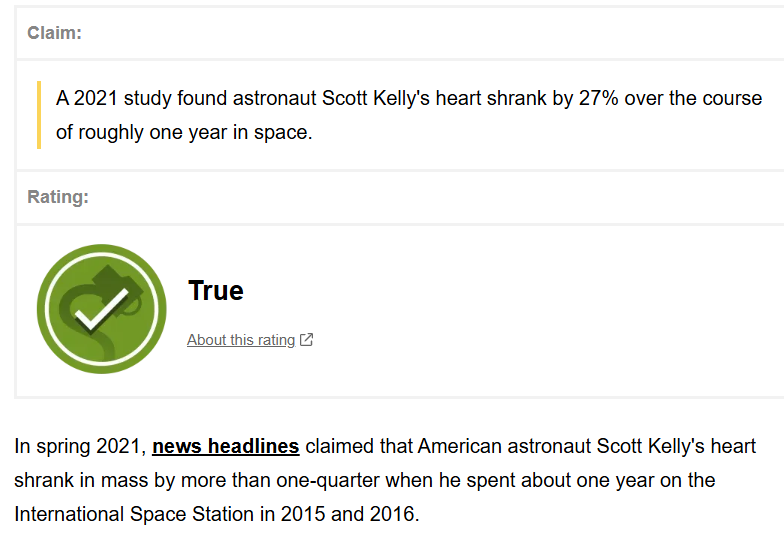

The news stories were purportedly based on a study published in the journal Circulation, a research arm of the American Heart Association (AHA) that publishes peer-reviewed research about cardiovascular health and diseases.

Using the journal's website, we determined the research to be authentic. We obtained a copy of the study's summary, titled "Cardiac Effects of Repeated Weightlessness During Extreme During Swimming Compared With Spaceflight," which was published on March 29, 2021, and explained the key findings of the research project attempting to determine the effect of Earth's gravitational pull on the human cardiovascular system.

Led by Dr. Benjamin Levine, a professor of internal medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Texas Health Presbyterian Dallas, the researchers analyzed the left ventricle (LV) of two people's hearts: Kelly's and that of Benoît Lecomte, a long-distance endurance swimmer who attempted to cross the Pacific Ocean in 2018. (Note: The left ventricle is the biggest and strongest of four heart chambers, pumping oxygenized blood throughout the body.)

The experiment looked at Kelly's heart before, during, and after his space trip -- he exercised almost every day in space to avoid losing muscle mass -- as well as studied Lecomte's cardiovascular system over the course of his 159-day swim. The researchers concluded:

"LV mass declined at similar rates in both individuals. B.L.’s mass dropped by 0.72 g/wk (95% CI, −0.14 to 1.58) and S.K.’s mass dropped by 0.74 g/wk (95% CI, 0.13–1.34) when linear regression is applied."

In other words, despite both men's physical activity, their hearts shrank at rate of about 1/40th of an ounce each week (0.72 g/wk for Lecomte and 0.74 g/wk for Kelly).

For the swimmer, that meant his left ventricle lightened from an estimated six ounces to five ounces over the course of his long swim. “I was just shocked,” Levine told The New York Times of that finding. “I really thought that his heart was going to get bigger. This was a lot of exercise that he’s doing.”

As for the astronaut, his heart size similarly decreased, showing a 27% decline in mass overall, as shown via the study's graph documenting the sizes of the two men's left ventricle over time (displayed below). Kelly's left ventricle went from 6.7 ounces to 4.9 ounces after the space trip, according to the experiment.

Earth’s gravity was undoubtedly a factor in the way human muscles evolved. The heart, for example, has to be strong enough to pump blood upward from the feet, where it would otherwise collect.

In low gravity, however, such muscles do not have to work so hard.

Since muscles must be exercised to remain healthy, and as preparations for extended missions are underway, scientists are concerned about the effect living in space can have on the human body.

A research letter from cardiovascular experts at the University of Texas Southwestern (UT Southwestern) examines the physiological effects spending 340 days in space had on Kelly.

Kelly’s heart shrank by an average of 0.74 grams per week during the year he spent in space, although the muscle continued to perform well.

Exposing human colonization of the Moon and Mars as Space Fraud, Waste and Abuse

© 2025. All rights reserved. SpaceFraud.Tech